Asymptotically flat spacetime

An asymptotically flat spacetime is a Lorentzian manifold in which, roughly speaking, the curvature vanishes at large distances from some region, so that at large distances, the geometry becomes indistinguishable from that of Minkowski spacetime.

While this notion makes sense for any Lorentzian manifold, it is most often applied to a spacetime standing as a solution to the field equations of some metric theory of gravitation, particularly general relativity. In this case, we can say that an asymptotically flat spacetime is one in which the gravitational field, as well as any matter or other fields which may be present, become negligible in magnitude at large distances from some region. In particular, in an asymptotically flat vacuum solution, the gravitational field (curvature) becomes negligible at large distances from the source of the field (typically some isolated massive object such as a star).[1]

Contents |

Intuitive significance

The condition of asymptotic flatness is analogous to similar conditions in mathematics and in other physical theories. Such conditions say that some physical field or mathematical function is asymptotically vanishing in a suitable sense.

In general relativity, an asymptotically flat vacuum solution models the exterior gravitational field of an isolated massive object. Therefore, such a spacetime can be considered as examples of isolated systems in the sense in which this term is used in physics in general. (Isolated systems are ones in which exterior influences can be neglected.) Indeed, physicists rarely imagine a universe containing a single star and nothing else when they construct an asymptotically flat model of a star; rather, they are interested in modeling the interior of the star together with an exterior region in which gravitational effects due to the presence of other objects, such as "nearby" stars, can be neglected. Since typical distances between astrophysical bodies tend to be much larger than the diameter of each body, we often can get away with this idealization, which usually helps to greatly simplify the construction and analysis of solutions.

Formal definitions[2]

A manifold M is asymptotically simple if it admits a conformal compactification  such that every null geodesic in M has a future and past endpoints on the boundary of

such that every null geodesic in M has a future and past endpoints on the boundary of  .

.

Since the latter excludes black holes, one defines a weakly asymptotically simple manifold as a manifold M with an open set U⊂M isometric to a neighbourhood of the boundary of  , where

, where  is the conformal compactification of some asymptotically simple manifold.

is the conformal compactification of some asymptotically simple manifold.

A manifold is asymptotically flat if it is weakly asymptotically simple and asymptotically empty in the sense that its Ricci tensor vanishes in a neighbourhood of the boundary of  .

.

Some examples and nonexamples

Only spacetimes which model an isolated object are asymptotically flat. Many other familiar exact solutions, such as the FRW dust models (which are homogeneous spacetimes and therefore in a sense at the opposite end of the spectrum from asymptotically flat spacetimes), are not.

A simple example of an asymptotically flat spacetime is the Schwarzschild vacuum solution. More generally, the Kerr vacuum is also asymptotically flat. But another well known generalization of the Schwarzschild vacuum, the NUT vacuum, is not asymptotically flat. An even simpler generalization, the Schwarzschild-de Sitter lambdavacuum solution (sometimes called the Köttler solution), which models a spherically symmetric massive object immersed in a de Sitter universe, is an example of an asymptotically simple spacetime which is not asymptotically flat.

On the other hand, there are important large families of solutions which are asymptotically flat, such as the AF Weyl vacuums and their rotating generalizations, the AF Ernst vacuums (the family of all stationary axisymmetric and asymptotically flat vacuum solutions). These families are given by the solution space of a much simplified family of partial differential equations, and their metric tensors can be written down (say in a prolate spheroidal chart) in terms of an explicit multipole expansion.

A coordinate-dependent definition

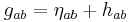

The simplest (and historically the first) way of defining an asymptotically flat spacetime assumes that we have a coordinate chart, with coordinates  , which far from the origin behaves much like a Cartesian chart on Minkowski spacetime, in the following sense. Write the metric tensor as the sum of a (physically unobservable) Minkowski background plus a perturbation tensor,

, which far from the origin behaves much like a Cartesian chart on Minkowski spacetime, in the following sense. Write the metric tensor as the sum of a (physically unobservable) Minkowski background plus a perturbation tensor,  , and set

, and set  . Then we require:

. Then we require:

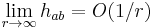

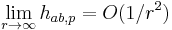

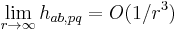

One reason why we require the partial derivatives of the perturbation to decay so quickly is that these conditions turn out to imply that the gravitational field energy density (to the extent that this somewhat nebulous notion makes sense in a metric theory of gravitation) decays like  , which would be physically sensible. (In classical electromagnetism, the energy of the electromagnetic field of a point charge decays like

, which would be physically sensible. (In classical electromagnetism, the energy of the electromagnetic field of a point charge decays like  .)

.)

A coordinate-free definition

Around 1962, Hermann Bondi, Rainer Sachs, and others began to study the general phenomenon of radiation from a compact source in general relativity, which requires more flexible definitions of asymptotic flatness. In 1963, Roger Penrose imported from algebraic geometry the essential innovation, now called conformal compactification, and in 1972, Robert Geroch used this to circumvent the tricky problem of suitably defining and evaluating suitable limits in formulating a truly coordinate-free definition of asymptotic flatness. In the new approach, once everything is properly set up, one need only evaluate functions on a locus in order to verify asymptotic flatness.

Applications

The notion of asymptotic flatness is extremely useful as a technical condition in the study of exact solutions in general relativity and allied theories. There are several reasons for this:

- Models of physical phenomena in general relativity (and allied physical theories) generally arise as the solution of appropriate systems of differential equations, and assuming asymptotic flatness provides boundary conditions which assist in setting up and even in solving the resulting boundary value problem.

- In metric theories of gravitation such as general relativity, it is usually not possible to give general definitions of important physical concepts such as mass and angular momentum; however, assuming asympotical flatness allows one to employ convenient definitions which do make sense for asymptotically flat solutions.

- While this is less obvious, it turns out that invoking asympotic flatness allows physicists to import sophisticated mathematical concepts from algebraic geometry and differential topology in order to define and study important features such as event horizons which may or may not be present.

Criticism

The notion of asympotic flatness in gravitation physics has been criticized on both theoretical and technical grounds.

There is no difficulty whatsoever in obtaining models of static spherically symmetric stellar models, in which a perfect fluid interior is matched across a spherical surface, the surface of the star, to a vacuum exterior which is in fact a region of the Schwarzschild vacuum. In fact, it is possible to write down all these static stellar models in a way which makes clear that they exist in plenitude. Given this success, it may come as a nasty shock that it seems to be very difficult, mathematically speaking, to construct rotating stellar models in which a perfect fluid interior is matched to an asymptotically flat vacuum exterior. This observation is the basis of the most prominent technical objection to the notion of asymptotic flatness in general relativity.

Before explaining this objection in more detail, it seems appropriate to briefly discuss an often overlooked point about physical theories in general.

Asymptotic flatness is an idealization, and a very useful one, both in our current "Gold Standard" theory of gravitation -- General Relativity -- and in the simpler theory it "overthrew", Newtonian gravitation. One might expect that as a (so far mostly hypothetical) sequence of increasingly sophisticated theories of gravitation providing more and more accurate models of fundamental physics, these theories will become monotonically more "powerful". But this hope is probably naive: we should expect a monotonically increasing range of choices in making various theoretical tradeoffs, rather than monotonic "improvement". In particular, as our physical theories become more and more accurate, we should expect that it will become harder and harder to employ idealizations with the same ease with which we can invoke them in more forgiving (that is, less restrictive) theories. This is because more accurate theories necessarily demand setting up more accurate boundary conditions, which can render it difficult to see how to set up some idealization familiar in a simpler theory in a more sophisticated theory. Indeed, we must expect that some idealizations admitted by previous theories may not be admitted at all by succeeding theories.

This phenomenon can be both a blessing and a curse. For example, we have just noted that some physicists hold that more sophisticated theories of gravitation will not admit any notion of an isolated point particle. Indeed, some argue that general relativity does not do so, despite the existence of the Schwarzschild vacuum solution. If these physicists are correct, we would gain a kind of self-abnegating intellectual honesty or realism, but we would pay a hefty price, since few idealizations have proven as fruitful in physics as the notion of a point particle (however troublesome it has been even in simpler theories).

Be this as it may, very few examples of exact solutions modeling isolated and rotating objects in general relativity are presently known. In fact, the list of useful solutions presently consists of the Neugebauer-Meinel dust (which models a rigidly rotating thin (finite radius) disk of dust surrounded by an asymptotically flat vacuum region) and a few variants. In particular, there is no known perfect fluid source which can be matched to a Kerr vacuum exterior, as one would expect in order to create the simplest possible model of a rotating star. This is surprising because of the plenitude of fluid interiors which match to Schwarzschild vacuum exteriors.

Indeed, if some argue that an interior solution which matches to the Kerr vacuum, which has Petrov type D, should also be type D. There is in fact a known perfect fluid solution, the Wahlquist fluid, which is Petrov type D and which has a definite surface across which one can attempt to match to a vacuum exterior. However, it turns out that the Wahlquist fluid cannot be matched to any asymptotically flat vacuum region. In particular, contrary to naive expectation, it cannot be matched to a Kerr vacuum exterior. A tiny minority of physicists (actually, a minority of one) appear to believe that general relativity is unacceptable because it does not allow sufficiently general asymptotically flat solutions (evidently this argument implicitly assumes that we have decisively rejected at least some Machian principles!), but a sequence of increasingly sophisticated and general existence results appears to contradict this assumption.

The mainstream viewpoint among physicists about these matters can probably be summarized by saying as follows:

- while many prominent researchers have tried to invoke Machian principles (including Albert Einstein and John Archibald Wheeler), the status of these principles, in contrast to widely accepted principles like the principle of conservation of momentum, is currently highly equivocal,

- general relativity admits a sufficient variety of solutions to model (in principle) any realistic astrophysical situation, plus (apparently) many highly unrealistic ones.

See also

References

- Hawking, S. W. and Ellis, G. F. R. (1973). The Large Scale Structure of Space-Time. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-09906-4.. See Section 6.9 for a discussion of asymptotically simple spacetimes.

- Wald, Robert M. (1984). General Relativity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-87033-2. See Chapter 11.

- Frauendiener, Jörg. "Conformal Infinity". Living Reviews in Relativity. http://relativity.livingreviews.org/open?pubNo=lrr-2004-1. Retrieved January 23, 2004.

- Mars, M.; and Senovilla, J. M. M. (1998). "On the construction of global models describing rotating bodies; uniqueness of the exterior gravitational field". Mod. Phys. LettARRAY 13 (19): 1509–1519. arXiv:gr-qc/9806094. Bibcode 1998MPLA...13.1509M. doi:10.1142/S0217732398001583. eprint The authors argue that boundary value problems in general relativity, such as the problem matching a given perfect fluid interior to an asymptoically flat vacuum exterior, are overdetermined. This doesn't imply that no models of a rotating star exist, but it helps to explain why they seem to be hard to construct.

- Mark D. Roberts, Spacetime Exterior to a Star: Against Asymptotic Flatness. Version dated May 16, 2002. Roberts attempts to argue that the exterior solution in a model of a rotating star should be a perfect fluid or dust rather than a vacuum, and then argues that there exist no asymptotically flat rotating perfect fluid solutions in general relativity. (Note: Mark Roberts is an occasional contributor to Wikipedia, including this article.

- Mars, Marc (1998). "The Wahlquist-Newman solution". Phys. Rev. D 63 (6): 064022. arXiv:gr-qc/0101021. Bibcode 2001PhRvD..63f4022M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.63.064022. eprint Mars introduces a rotating spacetime of Petrov type D which includes the well-known Wahlquist fluid and Kerr-Newman electrovacuum solutions as special case.

- MacCallum, M. A. H.; Mars, M.; and Vera, R. Second order perturbations of rotating bodies in equilibrium: the exterior vacuum problem This is a short review by three leading experts of the current state-of-the-art on constructing exact solutions which model isolated rotating bodies (with an asymptotically flat vacuum exterior).